Do Markets Have Memories?

Visiting a modern Stonehenge prompts questions about memory and regeneration

My memory is not what it was—and I very much doubt that I am the only Boomer concerned about such matters. Indeed, as societies age, they show growing interest in (and agitation about) memory loss. In response, the media world throbs with intense debates (or, more accurately, feeding frenzies) triggered by questions about how much emerging treatments for Alzheimer’s and other dementias will cost and who will pay.

Longer term, we may work out how to regenerate faded or even lost memories, though that seems like the stuff of science fiction today. Meanwhile, what holds true for individuals and families can also apply to societies and to markets. They, too, can suffer from amnesia, even dementia. As they lose their memories, our societies can also lose their sense of identity—becoming easier prey for ideologues.

Indeed, when autocrats and dictators want to unhinge us, among the earliest casualties are historians brave enough to recall lessons from the past that challenge the new ideologies. Healthier societies tend to have a clear-eyed sense of their own evolution and history. Which suggests several questions about how successful societies and markets recollect, how they forget—and how we can identify and treat outbreaks of market amnesia and dementia.

Total Recall Versus Full-Blown Amnesia

None of this is particularly novel. Indeed, I have touched on the theme in earlier posts like those on Minsky Moments (whose ability to surprise generally reflects societal and financial amnesia), on insurance and reinsurance (where accurate assessment of future risks depends on an understanding of past trends and their financial effects), and discounting—where those doing the discounting may recall the consequences of similar adventures through history but choose, for whatever reason, to ignore or downplay their likelihood and possible impact.

But if markets are conversations, as I argued in a post provoked by this year’s World Energy Council event in Rotterdam, titled “Redesigning Energy for People and Planet,” then we should think in terms of a spectrum running from almost total recall through to various forms of market amnesia—and even dementia. Positioned at various points across the spectrum, market actors try to inform today’s decisions with knowledge drawn from the past, the present and, through scenarios, modelling and other means, the future.

In terms of our history, one solution has been to selectively remember the past by putting old, semi-extinct industries and trades on show in museums. Visit regions where different livelihoods were once dominant, and you find yourself encouraged by leaflets and signs to visit museums celebrating—or at least recording—the relevant histories.

So, for example, while prowling the back lanes of Dorset last week, we visited the Cider Museum in Owermoigne. It calls to mind very different social hierarchies and realities, including the stories of the long-since-vanished armies of workers who once toiled to bring in the harvest for whoever happened to own the land at the time.

Such visits can underscore how our values change over time. As a result, anyone working in the history industry knows that society has periodic flashbacks that can force the reinterpretation of realities we had taken for granted. Nowadays, for example, most of us will disapprove of earlier generations of farm workers being paid part of their wage in cider, but no doubt some were grateful for it at the time—even where their families were not.

History looks different when viewed from the distance of a generation or two—particularly by those who have grown up in different geographies and cultures. So, in addition to all the other challenges they face, the directors and curators of many museums, galleries and collections are now struggling to take on board the role of colonization, slavery and other forms of exploitation in creating the wealth that later crystallized out in the great estates, stately homes and other buildings, art collections and monuments that their own livelihoods now depend on having people visit.

Such expressions of wealth can tell us a great deal about historic patterns of privilege and power. Sciences as various as geology, archaeology, palaeontology and genetic analysis are evolving continually, providing radically new insights. But the relevant information and knowledge are not easy for most people to unlock—and the lessons they can teach can be hard to access.

The scale of the challenge is underscored by the sheer amount of computer memory the world now enjoys. According to Statista, the world generated 33 zettabytes of data in 2018 alone. For those who like unimaginably big numbers, a zettabyte is 2 to the 70th power bytes, which can also be expressed as 1021(1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 bytes) or 1 sextillion bytes.

In terms that are slightly easier to grasp, that is equivalent to 660 billion Blu-ray discs, 33 million human brains, or 330 million of the world’s largest hard drives. And by 2020 the overall datasphere had reached 64 zettabytes, doubling in size every year.

Memory Stones

But if we are now cracking our memory storage issue, paradoxically, the question of how to access all that information in a meaningful way gets progressively harder. One way to do this involves a society—or at least a group of people—deciding to construct a mechanism that, once decoded, can help visitors or viewers capture a meaningful sense of the state of knowledge at a particular point in time.

We attempted that four decades ago when the team compiling the Gaia Atlas of Planet Management decided to bury a time capsule in the foundations of the new Prince of Wales Greenhouse, then being constructed at Kew Gardens. I tell that story, on pages 116-118 of my latest book, Tickling Sharks, describing how Sir David Attenborough lowered the time capsule into the hole on a chain with our two small daughters wearing ill-fitting hard hats and sitting on his knees.

At any moment, we are surrounded by multiple time capsules, some natural, others manmade. Objects that, viewed in the right way, can transport us to other times, other values. Among the manmade variety, one of the oldest in Britain is the Stonehenge complex, offering clues as to how the Neolithic cultures of the day saw their world—and their roles in it. Similarly, the pyramids that the ancient Egyptians began building not long afterward have given us profound insights into the evolution and priorities of Nile-side cultures.

All this surged to mind when we visited a more recent monument, indeed one erected just last year. I knew it existed, but in the end, we stumbled across it. Ignoring warnings from other visitors to the area that the place was “weird,” we zoomed our electric car across the great curving causeway to Portland Bill, Dorset, a peninsula arcing out from England’s south coast.

There, with the extraordinary panorama of Chesil Beach fanning out behind us, we walked around and through the Memory Stones. Like a smaller, more ragged version of Stonehenge, the twelve stones conjured by artist Hannah Sofaer collectively weigh in at around 250 tons. That’s pretty heavy by the standards of today’s computers, so what information is on offer?

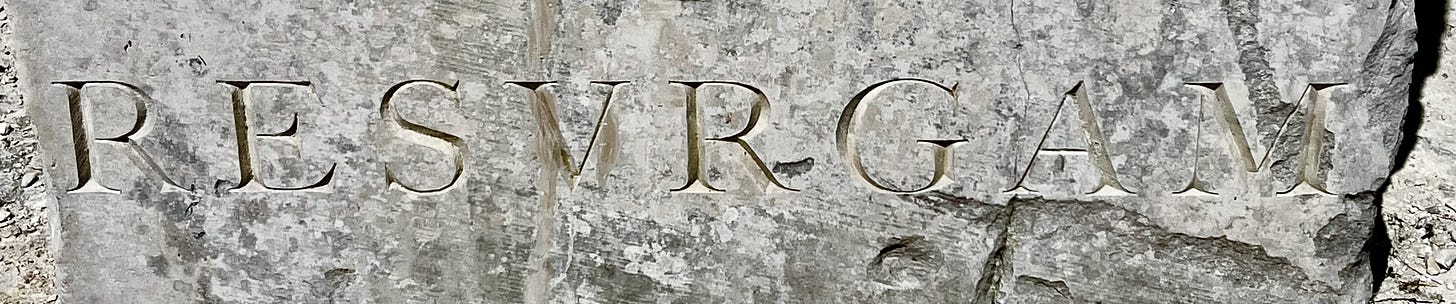

Each stone recalls a different element of local history—all in the spirit of regeneration, signalled by the single word RESURGAM (literally, “I shall rise again,” or in today’s vernacular, perhaps, “I’ll be back!”) carved into the outer face of the Wren Stone. This stone commemorates the use of Portland stone from nearby quarries by Sir Christopher Wren in his St Paul’s Cathedral and over 50 other churches he designed.

But the data storage is symbolic, not digital. A couple of the early stones in the circle hark back to the Triassic geological period that so powerfully shaped this part of what is now known as the Jurassic Coast. And a third column, the Ocean Stone, celebrates the world ocean, referring out to a Greenpeace project that involved dropping large blocks of Portland stone into the English Channel to deter fishing vessels from exploiting protected areas of the seabed.

This stone, covered in giant carved ripples, faces out to sea—in the direction of Greenpeace’s underwater barrier. The carved text reads as follows:

Stand with your back to this stone and look out to sea. 307 miles southwest of here lies an underwater barrier of boulders like these protecting the ocean from destructive industrial fishing and, with it, all of our futures. This ocean stone commemorates the collaboration between the Portland Sculpture and Quarry Trust and Greenpeace defending and safeguarding the UK's marine protected areas in an ocean that has sustained life for millions of years.

The Ocean Stone stands alongside a fourth spotlighting the story of the many quarries that now pock-mark Portland Bill, itself then followed by a fifth celebrating the archaeology carried out to explore a nearby Mesolithic site and a sixth spotlighting the contribution of Portland stone to world architecture, of which more in a moment. The remaining stones celebrate various forms of wildlife, among them the lichens, plants, insects, vertebrates (particularly small mammals and reptiles) and birds typical of the area.

The Portland Stone Age

The history of Portland Stone, the subject of the fourth Memory Stone, has long fascinated me, not least because much of my home city of London is built of it. Closest to home, in recent years, has been Somerset House, itself faced with Portland stone. Volans has been based there for some years. The nature of its façade was called to mind recently as various types of equipment impeded entrance during the deep cleaning of the stone.

Portland stone’s combination of brilliance and durability has led to its being used in everything from the UN headquarters building in New York, which I have visited several times, through an ever-expanding litany of London buildings like the British Museum, the National Gallery, the Bank of England, both sides of Regent Street and the BBC’s Broadcasting House.

In fact, the use of this stone can be tracked back at least a thousand years, with one recorded use being for Exeter Cathedral back in 1300—for a total cost at the time of ten shillings. No doubt you could calculate how much money has been earned from extractin

g and using Portland stone over the centuries, but that task is beyond my current ambition and resources.

Still, commercial use of the stone really took off after the Great Fire of London in 1666. Portland stone was widely used in the reconstruction process, a phoenix-rising-from the-ashes story that is referred to on the outward-facing side of the Wren Stone. Astonishingly, St Paul’s Cathedral alone is estimated to have used 3 million cubic feet of the stone.

Again, if you have the eyes to see, you will know that many war memorials were made from Portland stone, including the Cenotaph and—most recently—the Bomber Command memorial near Hyde Park Corner. Inevitably, though, the stone has been used to memorialize people whose records are, to put it mildly, contested. One such example has been the Cecil Rhodes monument at Oxford University’s Oriel College.

Portland stone itself is a form of time capsule, containing evidence of goings-on in the warmer seas of the Jurassic, when huge volumes of carbon dioxide were captured by organisms from the atmosphere overhead, over extraordinary expanses of time. Indeed, travel further along the Jurassic Coast and you get an extraordinary sense of that story from The Etches Collection, whose remarkable prize exhibit—the skull of a Pliosaur, popularly known as “Sea-Rex”—was celebrated in a TV program hosted by none other than David Attenborough.

Can Portland Go Green?

So, what are the environmental credentials of such a widely used material? One great advantage of Portland Bill’s location was that stone could be taken to distant markets by sea. Unsurprisingly, too, if you visit the websites of Portland stone companies, you very soon come across the word sustainability, together with a variety of green certifications covering things like air quality, energy efficiency and waste management.

As to the ultimate sustainability question of whether and when Portland Stone will run out, there are several complicating factors. One is that the use of thinner stone slices for façade work, not least to cut costs, means that there will be more left for future projects. Half of Portland’s stone has already been excavated, it is estimated, but if the rate of extraction remains constant, there should be enough left for another 1,000 years.

Intriguingly, meanwhile, demand for the stone is being squeezed by the cleaner air in cities like London. According to Michael Poultney of Albion Stone, a company that has been producing the material since 1927, “pollution is so low in London compared to what it was when coal fires roared and factories lined the Thames that not a lot of stone is weathering away, so the amount we’re supplying for restoration is about a bucketful, to be honest. Together with most of the industry, we rely on new builds, it’s 99 per cent of our work.”

Eventually, though, Portland stone must run out. Already, the original open pit quarries have been supplemented by deeper mines as layers of the best stone are pursued into the depths. Then, as the older quarries are worked out and abandoned, they are being turned over to a range of new uses, from holiday caravan parks to wildlife reserves—of which I was most inclined to wander around the latter.

Anyone wanting to get a sense of how the natural regeneration of such sites can proceed—and be sensibly accelerated—would be well advised to take a look at the related work of the Dorset Wildlife Trust on Tout Quarry, a few moments’ walk from the Memory Stones.

But on my original question, as to whether markets have memories, the answer must be that yes, they can do—though generally those memories are lodged in the brains of mortal human beings. Filing and data systems are often only as good as the people who know—or knew—how to use them. And the speed with which corporate memories are eroding has accelerated as staff turnover has sped up.

Ultimately, then, and even when AI becomes pervasive, this deeper form of market intelligence will likely always depend on the curiosity of individuals—discovering what they can and then sharing what they find across their networks. The spread of the internet, and of platforms like Wikipedia, potentially means that a growing proportion of this knowledge is potentially discoverable. This brief account of a very personal exploration of market memory, triggered by that first visit to the Memory Stones of Portland Bill, is posted here in that spirit.

Really like this article John, thought provoking, insightful about a stone I really like👍🏻

The very, very long now we call stone.