The Pursuit Of Transparent Markets

Generation Investment Management concludes that tomorrow's sustainability reporting must be integrated, contextual, comparable - and mandatory.

In a world increasingly travelling down the capitalist road, I concluded early on that sustainability would be impossible without transparent markets. They would not be a sufficient condition for progress but, unquestionably, they would be a necessary condition. And I argued publicly that voluntary disclosure initiatives would be an effective way of softening up the opposition.

Get the pioneers to disclose, then force the laggards to catch up—and, a key trick, rank their performance along the way. That’s something I worked on for many years with the UN and with the embryonic Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes (DJSI).

Now, as geopolitical hostilities sizzle and globalisation stutters, it is worth considering whether this basic principle still holds true—and I think it does. But wider thinking on the subject has been evolving significantly, as underscored in a new publication from our longstanding friends at Generation Investment Management.

Their latest paper focuses on the global spread of sustainability disclosure and concludes that “a global revolution in sustainability disclosure is under way. Regulators across the world are developing rules that will compel businesses to report on an unprecedented array of sustainability issues, including their greenhouse-gas emissions, as well as on climate-related risks and opportunities.”

Beyond that evolving market reality, Generation says that it strongly supports “implementing a global baseline of mandatory sustainability-disclosure requirements.”

The good news here is that the newish EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) promises to be an important step in that direction. But, as I argue in the latest issue of Germany’s Reporting Times, we may now see the supply of sustainability data and information forcefully outpacing meaningful demand.

Don’t allow lawyers to run the show

That said, and contrary to many people, I would argue that we have made massive strides in opening up business to related change agendas. My concern, though, is that we will end up trying to tackle systemic challenges with incremental and increasingly compliance driven solutions. Lawyers are fine, in their place, but—time and again—I have seen their influence hugely cramp innovation in major companies.

So perhaps it’s time to look well beyond what keeps the legal profession happy to the sorts of disruptions needed to prepare today’s markets for tomorrow’s realities? In that spirit, this post is the first in a planned Substack series designed to prepare the ground for the launch of my twenty-first book, Tickling Sharks: How We Sold Business on Sustainability, due out on 18th June. (The plan is for it to launch simultaneously in hardback, paperback, audio and Kindle formats.)

One theme that threads through the entire book is that of the long-running—and in now intensifying—battles to open up business to discussions around safety, health, environment, sustainability and, specifically where, climate.

For me, all this began literally half a century ago with my writing for New Scientist, covering companies like British Gas and English China Clays. This, in turn, led to my being invited to co-found Environmental Data Services (ENDS) back in 1978, and edit the embryonic ENDS Report. I visited scores of companies during this period, helping open them up to the wider change agenda—even though most of them were then convinced that anything with an environmental tag was probably going for their corporate throat.

Activist groups like Greenpeace had got their attention, no question, but most of them had concluded that if there was one group of people they didn’t want to talk to, alongside Communists, it was Greenpeace and the like. Our self-set question at the time was how we could make such engagement the norm—and that is precisely what we did through the Eighties and into the Nineties.

Shortly after we launched ENDS, paradoxically, we found ourselves helping companies like BP and ICI draft their first environmental policy statements. Then, in our 1987 book Green Pages: The Business of Saving the World, I compiled the world’s first-ever review of the coverage of safety, health and environmental issues in corporate annual reports.

Later that same year, I laid out some of the transparency and accountability challenges for business in The Green Capitalists. But the big shift really began when my third company, SustainAbility, began to work on the first generation of corporate environmental reports, alongside partners like the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu International (DTTI) and the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD).

Voluntary approaches won’t crack it

After I had launched the triple bottom line in 1994, we expanded the focus of our challenge to embrace wid er sustainability reporting—kickstarting that agenda with our 2-volume 1996 report, Engaging Stakeholders. Even so, I recall a senior executive with Shell telling me quite forcefully that the oil giant would never report in this way—because it was too big and too complex.

Paradoxically again, within a year we were helping pioneering companies like Novo Nordisk and Shell to compile their first sustainability reports. We also supported the evolution of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), launched in 1997. (Indeed, it was wonderful to host GRI co-founder Bob Massie at our home in London a few weeks back.)

Later still, I got involved with the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), as a Council member for three years, and—since 2007—with EcoVadis, the supply chain transparency platform where I continue to be involved.

But, while such voluntary initiatives have certainly helped prepare the ground, as Generation accepts, helping bring “market participants—and other stakeholders—together to agree on topics and metrics that matter,” the voluntary approach only takes us so far. As their paper warns, “so long as disclosure is voluntary, there is no level playing field.”

The paper notes that, “Many investors (including Generation) have over many years worked together to encourage and develop voluntary standards. The IFRS Foundation, the not-for-profit responsible for developing global accounting and sustainability disclosure standards, has diligently worked on these standards. These voluntary standards have formed the basis of the IFRS’s new board, ISSB (International Sustainability Standards Board), which is now proposing mandatory standards.”

The coming boom in climate-related disclosure

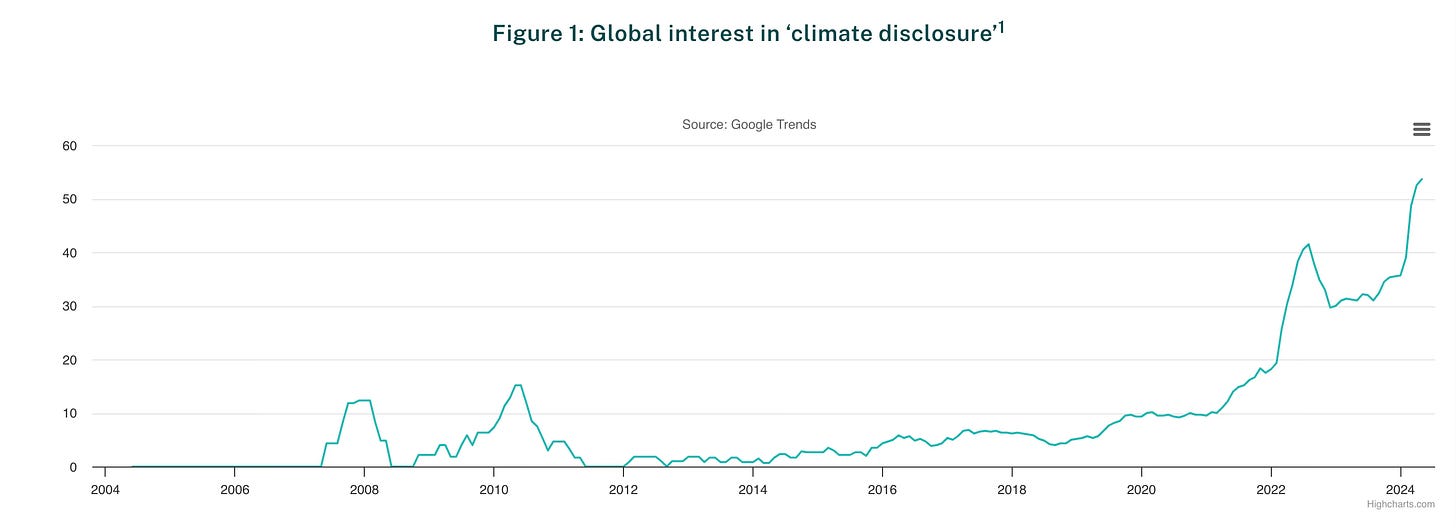

The new Generation paper covers a sub-set of sustainability reporting, mainly focused on climate-related disclosures. And their first diagram, shown below, usefully tracks global growth in interest in the agenda.

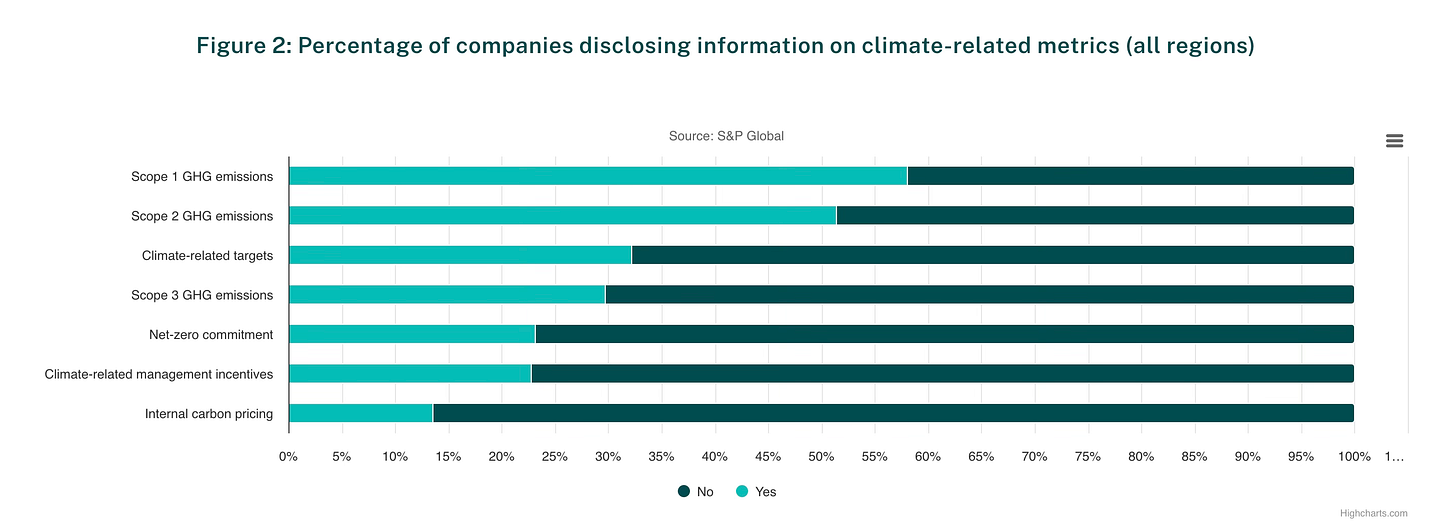

Their second diagram shows the spread in coverage of key issues in current corporate disclosures, with issues like internal carbon pricing mechanisms still trailing—while the disclosure of Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions is now moving powerfully into the mainstream.

We are making progress, clearly, at least on climate-related issues. But I am struck by the four main conclusions of the Generation paper. In headlines, and in addition to the disclosure-needs-to-be-mandatory point already covered, they are as follows:

First, reporting must be integrated. “The value an entity creates for itself and its investors is inseparable from the value the entity creates for other stakeholders, society and the natural world. And a company’s impacts on its stakeholders can create risks and opportunities for that company.”

Second, reporting must be context-related. “Sustainability information only provides insight when it is set in the wider context of planetary boundaries and related social and ecological thresholds.”

Third, reported performance must be comparable. “Globally comparable information matters. Most investors have global portfolios and most companies have global value chains. Investors benefit from disclosure because it allows them to compare companies and then allocate capital to those that have the greatest chance of success.”

And, fourth, critically, key reporting and disclosure standards must be mandatory. As Generation concludes, “The companies we like most are those actively contributing solutions, but regardless we expect all the companies in which we invest to act to avoid harm to their stakeholders. If some companies but not others disclose how they are (or are not) managing their negative impacts, it makes it harder for more sustainable business models to position themselves.”

A parting shot

As a parting shot from me, some readers may recall the image I had Financial Times cartoonist Ingram Finn do way back in 1991—illustrating the space I would eventually try to fill with the triple bottom line in 1994 and the People, Planet & Profit formula in 1995.

I has asked that the cartoon show a fish in a business suit, a woman from the Global South and a robot all sitting around a boardroom table, symbolising the need to engage champions of natural capital, social capital and the deep future. I have used it in many hundreds of presentations over the years and, unsurprisingly, it now enjoys pride of place in Tickling Sharks:

Well, always pushing the envelope, I put more or less the same instructions in to the AI-based design platform Artiphoria a week or so ago—and found the result rather striking. The most notable change is that the woman has gone from being marginalised and poor to professional and assertive.

Significantly, too, the information all three are immersed on is now digital and pervasive. When Ingram literally put pen to paper, the Internet was still several years in the future for most of us.

Now Generation’s thinking can help us all make sense of this emerging reality, though the rise of countries like China and India should not blind us to the continuing scale of absolute poverty in regions like Africa—aggravated by pandemics, corruption and, increasingly, conflict.