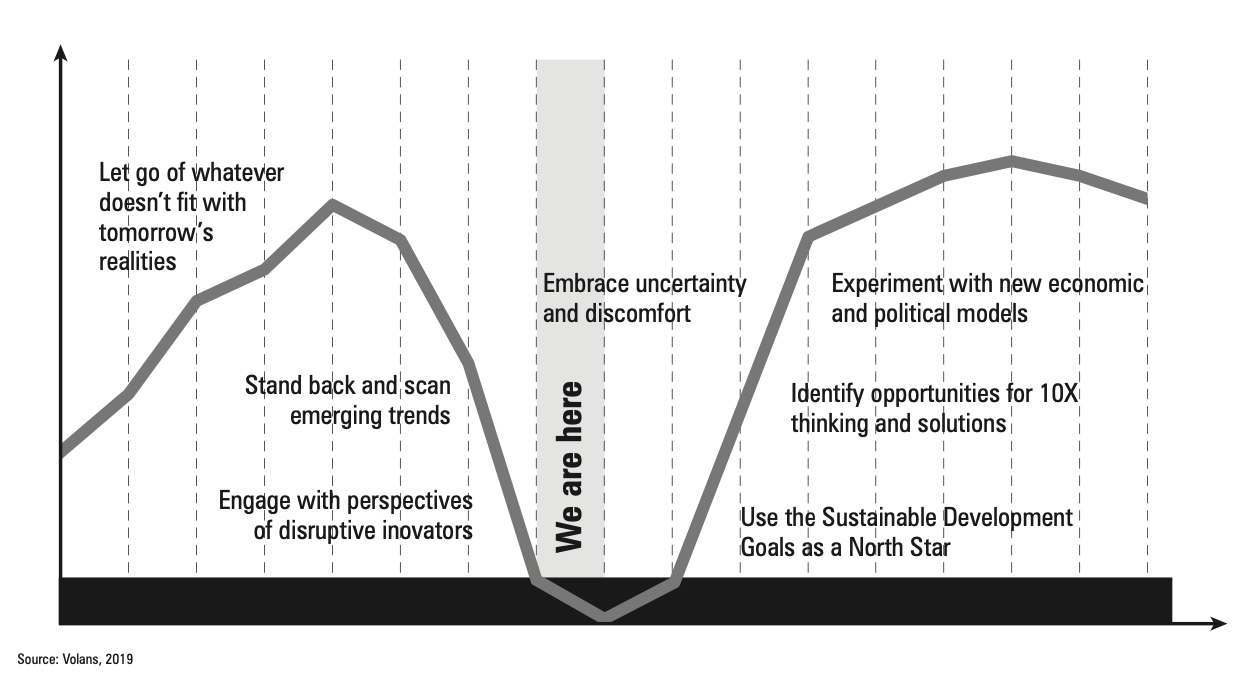

Periods of globalization eventually come to an end, either slowly or abruptly. If history is any guide, they tend to be derailed by growing protectionism, regionalization and conflict. Hence my conclusion that the world was headed into a gigantic “U-Bend,” spotlighted in the first illustration (see below) in my 2020 book, Green Swans.

My uncomfortable conclusion was that looming shifts in geopolitics and macroeconomics would sideswipe much of our sustainability agenda, before eventually opening up the prospects for truly transformative change.

I very much doubt that globalization as we have known it will grind to a complete halt in the next few years, but its character is beginning to change profoundly—with profound implications for the market context within which business operates.

I am even more concerned today that we are seeing every sign of an accelerating shift from the highly integrated, liberalized economic system that has dominated our lives since the late twentieth century to an increasingly fragmented and contested model of global interaction.

The obvious implication: Anyone thinking about corporate responsibility, the climate and biodiversity emergencies, the circular economy or sustainability without considering these wider shifts risks being driven off the road. Worse, they may miss the opportunities to help reshape the emerging economic order.

So why is this happening—and why is it happening now? Among key trends pushing us in this direction are the following:

1. Regionalization

This trend is being spurred by the rise of regional trade blocs. Agreements like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) all emphasize regional cooperation over global integration.

A linked driver will be the desire for shorter, less vulnerable supply chains. Already, we see businesses reshoring or nearshoring production to mitigate risks from global disruptions like pandemics and geopolitical conflicts.

2. Geopolitical fragmentation

The evolving US-China rivalry will be a central concern , with escalating competition between the world’s two largest economies driving decoupling in technology, trade, and finance.

Even on its own, this will increasingly split the global system into competing spheres of influence. At the same time, however, the incoming Trump Administration shows every sign of weaponizing trade, using economic sanctions, tariffs, and export controls as geopolitical tools, all of them helping to disrupt global trade flows.

3. Economic protectionism

We see a huge resurgence in interest in industrial policy, with both good and bad implications. Countries like China and the US, alongside trading blocs like the EU, increasingly focus on domestic manufacturing and what are increasingly considered to be “strategic” industries, among them semiconductors and green energy. As part of these shifts, governments are imposing measures to protect local industries, further squeezing cross-border trade.

4. Supply chain realignment

The great globalization wave that has shaped so much of our lives in recent decades largely focused on boosting efficiency. Now, by contrast, we see growing concerns about resilience, which I flagged in Green Swans.

Among key factors here have been the Covid-19 pandemic, the Ukraine conflict, and a growing number of natural disasters, all prompting companies to prioritize resilience over cost efficiency. This, in turn, has often led to the shortening and simplification of supply chains.

A parallel trend has been the growing competition for critical natural resources. Often spurred on by their ambitions for their proposed green transitions, nations are scrambling to secure rare earth minerals, food supplies, and energy resources, once again leading to enhanced trade barriers—and to new alliances designed to secure access to mission-critical resources.

5. Technological decoupling

A key issue here, often driven by cyber hacking by individuals and increasingly states, has been the growing interest in reinforcing digital borders. As a result, countries are trying to regulate data flows, technology transfers, and digital ecosystems.

Divergent standards for emerging technologies such as semiconductors, 5G telecommunications and AI, are likely to further fracture the global system. Governments, meanwhile, are increasingly prioritizing domestic control of critical technologies to reduce reliance on current and possible future adversaries.

6. Environmental imperatives

Too often, environmental and sustainability considerations will be used as alibis and camouflage for some of the shifts highlighted above. But as global realities press in, among them the growing tempo and severity of natural disasters, the push for carbon neutrality and reduced emissions will accelerate moves toward regional and sustainable supply chains and energy systems.

And there will be consequences, some intended, others not. Already there are concerns that new types of carbon tariffs—among them initiatives like the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, or CBAM—could create green trade barriers.

7. Weakening global institutions

As if all of this were not enough to be getting on with, we also see waning faith in the whole idea of multilateralism. Institutions like the WTO, IMF, and UN face growing criticism for failing to address the growing number of systemic challenges now pressing in, leading nations to bypass global frameworks in favor of bilateral or regional agreements.

The incoming Trump Administration, even if increasingly riven by its own internal contradictions, looks set to aggravate all these seven trends.

None of this necessarily means a complete end to globalization, but taken together such trends do suggest a shift toward "deglobalized" or "regionalized" forms of globalization—shaping a new system that is simultaneously more localized, more strategic when viewed from the perspective of individual countries or blocs, and—overall—is less reliant on universal interdependence.

Among the implications, we should expect to see a growing focus on:

· Regional hubs: With regional powers like the EU, ASEAN, and the African Union taking the lead in trade and policy.

· Strategic alliances: The emphasis here will increasingly be on partnerships based on shared security or resource interests, such as the Quad or BRICS+.

· Selective globalization: Although trade and cooperation are likely to continue in critical areas, such as climate change, healthcare and some aspects of technology, this will happen in the context of frameworks that are, somewhat paradoxically, both more controlled and more fragmented.

By 2030, the coming tariff wars will have reshaped key aspects of the economic landscape. Already we see Chinese auto-makers working out how to do end-runs on existing or incipient trade barriers. So we should expect major companies to set up more production hubs behind trade barriers, as when Chinese businesses set up new sites in the EU, or EU businesses set up new sites in the US.

The distraction effect of all this on business leaders will be considerable—and the impact on the sustainability agenda can only be profound.

So, our challenge now will be to ensure that our organizations, platforms and alliances are resilient enough to survive what will now be thrown at us, while at the same time reconfiguring our own partnerships in such a way that we are well prepared to ride the next upwave of economic change.

For me, at least, that will be a core priority through 2025 and, hopefully, beyond.

John Elkington is Founder & Chief Pollinator at Volans. His personal website can be accessed here. This post draws on the Coda & Manifesto section of his new book, Tickling Sharks: How We Sold Business on Sustainability (Fast Company Press, 2024). This 10-part series of posts is designed to run daily from the 2nd to the 6th of September and the second five from the 9th to the 13th of September.

Available on Amazon and through good bookshops:

What readers say:

“John is a legend. Throughout my 30-year career in sustainability leadership, he has been a source of insight and inspiration. By extension he has influenced the thinking of thousands of senior executives on our programmes. This book offers a wonderful and personal reflection on the evolution of the sustainability movement and glimpses of what might be to come.”

DAME POLLY COURTICE, founding director, Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL)

Thank you for your article. I wonder whether what we are experiencing is a necessary Globalization change. The Globalization up till now has been about extracting resources and wealth from South to North ignoring totally the local and regional needs of the population in the South. At the same time a total ignorance of balanced relations to nature. It poses certainly new challenges to industry not only in the North but also in the South. Up til now industrial and agricultural development in the South has been (to a large extent) directed towards fulfilling the needs in North. To change this and at the same time keep the focus on Thriving solutions is a huge task. At the same time this might be possible with a changed perspective from BIG to SMALL, from Growth in GDP to Growth in well-being or Thriving.

I agree