The Anthropocene: What's In A Name?

As life on Earth adapts to a species that wants it all, some thoughts on what's coming

Visualizing the future is a critical task in system change—and one of our team’s favourite system change mapping tools is the Berkana Institute’s Two Loop diagram. It illustrates how paradigms shift, with an older system failing and decomposing—despite the increasingly frantic efforts of “stabilizers”—and a new one (or new ones) evolving.

The Loops diagram comes in different versions, but we like this one:

Not all versions include the first step shown here on the orange “Emergent System” trajectory: Naming. But it’s crucial. People living through the “Renaissance” didn’t know that this was what they were living through, with the term emerging later and being variously attributed, among others to Giorgio Vasari in 1550.

Most people at the time experienced chaos and disorder, with little sense of any overall direction. Ditto most people living through the “Industrial Revolution”, a term tracked back to a French economist in 1799. Such tags often come later, when people begin to see bigger pictures.

But name something in the right way and the future can seem more comprehensible. Consider Al Gore’s comment some years back that, “The sustainability revolution has the magnitude of the agricultural and industrial revolutions but the speed of the digital revolution.” That’s a positive, upbeat framing—whereas some framings focus instead on the challenging sides of the equation.

One such as been the concept of the Anthropocene epoch, which I understand to mean the first era in Earth’s evolutionary history where a single species—our own—has planetary effects equal to (or exceeding) geological forces. For me, the best summary of the potential significance of the concept was published by The Economist in May 2011, though that’s now behind a paywall. A briefer definition comes from the National Geographic Society—and has the virtue of being free.

So are we now in the Anthropocene?

Not so fast, says one key group of scientists reviewing the subject—for more details see here. Among their reasons for disputing the label, they explain, is that we are really talking about an “event”, not a geological “epoch”—and it began well before the 1950 start date that many scientists have claimed for the Anthropocene.

The original reasoning was that the 1950s saw the international spread of open-air nuclear bomb tests, leaving an unmistakable and readily identifiable imprint on the planet, alongside the rapidly accelerating use of novel—and durable—materials like plastics and “forever chemicals”.

As to an earlier start date for all this, in my 2020 book Green Swans I recalled the argument of UCL professors Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin, in their book The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene, that the Anthropocene actually began with the European colonization of the “New World” in the sixteenth century. As they concluded:

… the choice of start date for the Anthropocene will inevitably feed into the stories we tell about ourselves and wider human development. If the Anthropocene is pinned to the Columbian Exchange, the deaths of 50 million people, and the beginnings of the modern world, then it is a deeply uncomfortable story of colonialism, slavery and the birth of a profit-driven capitalist mode of living being intrinsically linked to long-term planetary environmental change. What we do to each other matters, as well as what we do to the environment. And given that nobody meant to transfer diseases that killed tens of millions, it is also a cautionary story: human actions can cause accidents with terrible consequences.

I knew about the impact of colonization on the original inhabitants of the Americas from books like Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel. But I recall being for forcibly struck by the latest findings that the resulting deaths of anywhere between 50 and 80 million indigenous people in the Americas triggered significant climate change even back then.

As the original people faded from the landscape, the forests recovered, sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere—with carbon dioxide levels reaching a distinctive minimum around the year 1610. This almost certainly aggravated the so-called Little Ice Age in the northern hemisphere.

Yes, I understand why so many scientists struggle when asked to label periods of planetary disturbance, particularly if asked to attribute human agency—however unwitting—to them. But I conclude that the political impact of embracing the Anthropocene labelling would be considerable and largely positive. Apart from anything else, it would help us think at different scales.

In my mind, our scientific paradigm (in the sense originally introduced by Thomas Kuhn in his 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions) began shifting in the late 1950s, catalysed by James Lovelock’s early work with the electron capture detector. Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, also published in 1962, built on that work. Then the emerging paradigm received an enormous catalytic boost from the spate of Earth-from-outside images produced by NASA in the Sixties and Seventies.

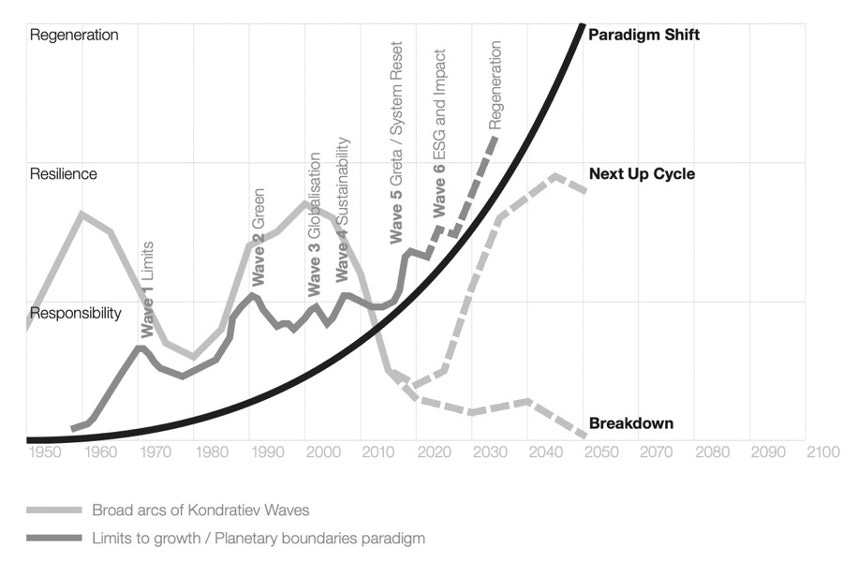

My take on where all this came from—and where it might be headed—is sketched in the following diagram, which I have been evolving since 1994. Underlying all the ups and downs in the change agenda, with period of progress often triggering contrarian movements, is this accelerating shift in our prevailing paradigm—summed up in the “take-make-waste” mindset—toward the acceptance of a new reality of planetary boundaries, circularity and sustainability.

Among the books in my to-read stack is Fareed Zakaria The Age of Revolutions. It tells “the story of progress and backlash, of the rise of classical liberalism and of the many periods of rage and counter-revolution that followed seismic change.” Increasingly, as we experience political recessions, among them the ongoing “ESG recession” and a likely “sustainability recession,” we must draw on historical analysis to ensure that we make the best of the once-in-a-lifetime change opportunities now opening up all around us.

In this sense, perhaps it doesn’t much matter what we call this emerging age of ours. Perhaps we should leave that to future historians to sort out? And it’s worth noting that the scientists tests who ruled against the Anthropocene labelling this time around stressed that that grim planetary reality remains the same—that we are accelerating into a period marked by unparalleled climate and biodiversity emergencies.

As far as the intricate mechanics of the decision go, a recent Washington Post article is illuminating. So how significant is the decision not to adopt the Anthropocene naming? To get a sense of what one leading scientist in the field thinks, I turned to Henrik Österblom, professor at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and director of the Anthropocene Lab in Stockholm. And I asked him whether the vote against the Anthropocene framing was a serious setback.

“The rejection is frustrating for sure,” he replied. “But mainstream science will always be slow. This technical decision doesn't actually change anything about the challenges or about what needs to be done. If anything, it makes me want to work harder!”

And that’s the can-do spirit that, in the Berkana Institute framing, will get us from today’s dysfunctional “Dominant System” into the critical stages of the “Emergent System”. While further political pushback is guaranteed, my sense (as argued in my impending book, Tickling Sharks) is that this latest paradigm shift—while existentially disconcerting for anyone with vested interests and stranded assets trapped in the old order—will move much further in the next 10-15 years than in the last 50.

Interesting directions. I wonder if we might create a further loop/cycle of centralised vs decentralised systems as part of the cultural evolutions (eg. old and poorly drawn, but illustrates my point https://flic.kr/p/7b4GqL)

Great piece, I also like your graphic. When exactly the Anthropocene started and whether it's an appropriate name to begin with, is, I think, less important than acknowledging we are The Dominant Species on the planet, capable of both destruction and regeneration.

I hope the next waves on the graphs will include hard policy to curb CO2 emissions, such as CTBO, and climate repair / regeneration.