2024, as already mentioned in this series of posts, marks my seventy-fifth year—and my fiftieth year of working professionally on the environmental and sustainability agendas. A period during which the movements and sectors I have been lucky enough to be involved in have driven change on multiple fronts and at many different speeds and scales—but always with the angst-inducing sense that the problems have been evolving faster than the solutions.

Writing Tickling Sharks, due out in June, has had me stress-testing many aspects of what I believe—alongside key elements of the theory of change I have evolved over time. Indeed, that’s one key reason why I have tried to unhook parts of my brain this year to explore new ways of driving change, with this new Substack series very much part of that process.

Then, yesterday, while taking a few days off in Normandy, France, we visited Honfleur—somewhere I have wanted to return to for around over 30 years. What had stuck in my memory was the architecture and urban planning, themes particularly close to my heart at the time. When I was doing my postgraduate degree at UCL, among other things, I had explored how communities responded to constraints, as when town and cities evolved within fortifications.

Nor did Honfleur disappoint this time around, though my brain did begin questioning where all that wealth had come from, back in the day.

A little effort online later on in the day suggested that two answers had been the trafficking of slaves from Africa to the Americas, and the exploitation of the fisheries of the Grand Banks off Newfoundland. As a result of sustained overfishing by vessels from around the world, among them crews from Normandy, the population of Northern cod on the Banks had fallen to just 1% of historic levels by 1992.

While in Trouville this week with our youngest daughter and her family, I have been freewheeling to an unusual degree, reflecting on intergenerational dynamics and developing a longer-than-normal presentation for Monday. This is for a virtual session on “the future of capitalism” attended by business executives—and organised by a number of leading business schools, including Japan’s Shizenkan University and Spain’s IESE.

As a result, various threads have been weaving together in my brain—and in the early hours of this morning I woke up with a clearer vision of what I would ideally spend the next few years working on.

Here’s the story, in headlines. For some time, I have been comparing the work of the growing global corporate responsibility and ESG (environment, social and governance) industry with the cleaning up of individual fish (i.e. corporations) before they are released back into polluted waters (i.e. dysfunctional markets, incentivising the wrong priorities and behaviors).

None of this is new for our team, indeed it’s a point we have been hammering home for years—but the key recognition last night was that, rather than just talking about it, I must now do more to address linked challenges. And I suspect that one key reason all of this has surfaced so forcefully was that I spent some time yesterday watching koi carp swimming around a pool inside the NaturoSpace butterfly farm on the outskirts of Honfleur.

Fish can’t see the water in which they swim, we are told. But businesses will increasingly need to be alert to how their markets need changing—and how they can best play a role in making that happen.

Over the decades, my colleagues and I have tried to shape markets in various ways, as in our Green Consumer work in the late Eighties and Nineties, our promotion of environmental auditing and sustainability reporting following on directly from that work, and my parallel efforts alongside pioneers in socially responsible investment, including the Merlin Ecology Fund, ING, Storebrand, Zouk Capital and the now-defunct Social Stock Exchange.

But the truth is that our corporate work has often paid better—and therefore has tended to attract more of our attention and effort. And even the most ambitious clients generally want to be responsible—and in a few cases to transform themselves—within the constraints of existing markets.

Happily, though, we have been lucky enough to attract funding from a range of foundations, including most recently the Porticus Foundation. They are supporting our ongoing work on ways in which individual companies can influence and pressure industry and trade associations that they are part of, to better align their climate policies with those of their most advanced members. This is a line of attack Volans has also taken with our latest report—with InfluenceMap and for Unilever. Its title: Climate Policy Engagement Review.

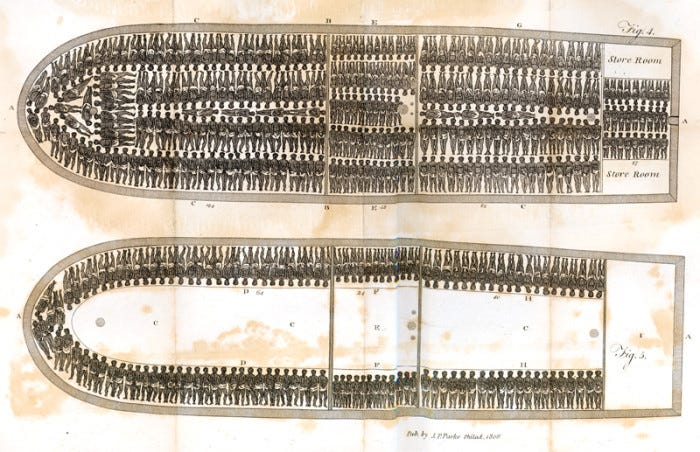

Once back home in Trouville yesterday, I dug into the history of former Normandy slaving ports like Honfleur, Le Havre and Nantes. In the process, I was confronted again with images that are beyond belief in today’s world. As it happens, too, one of the books I am working through at home currently is Breaking The Chains. In the same way we now view images like the one above with undiluted horror, I have been pondering again what aspects of today’s market dynamics future generations—including our own children and grandchildren—will view in like manner.

So, my self-set exam question now seems to be how tomorrow’s markets can be designed and operated to ensure that their impact is humane, responsible, sustainable and, ultimately, regenerative. In effect, how can we reinvent markets so that they serve tomorrow’s world, not just subsets of today’s world?

None of this means abandoning our corporate work, not least because it is an invaluable source of insights into how key commercial actors see the markets they aim to serve. But, for me at least, this does suggest a significant shift of emphasis in my own work. So, please do let us know if you are working in related areas—or if you know of related work by people or teams who we may not already be linked to.

Interesting question how future generations will look back on current market dynamics. Perhaps they will assume we were worshiping money? A bit like we assume people in the middle ages were devout Christians because they allocated so many resources to the construction of churches and cathedrals.

We at neighborhoodeconomics.org, formerly SOCAP are working in a way that is aligned with your new focus I believe.