Postgenerational Markets

Mauro Guillén's book 'The Perennials' offers a route to more sustainable economies

Somebody charmed me the other day by saying that I was their favourite perennial. It resonated because I had just finished reading Mauro Guillén’s book The Perennials on flights to and from Istanbul, where I also managed to pick up my second dose of Covid—despite having had all the vaccinations now offered to older citizens. The net result of all this was to have me revisiting my assumptions about the generational dimensions of the sustainability agenda.

The original idea was the sustainable development, fundamentally, about intergenerational equity. At worst, we should ensure that our choices do not leave future generations less well off—and, at best, we should work to improve the world they will inherit.

That, at least, was the original idea, though a lot of that has been lost in the wash. A key problem has been that—using highly distorting discounting methods—capitalism, markets and most market forms tend to define the conditions to be improved in terms of GNP, consumerism and life expectancy.

Using such metrics, a case can easily be made that our progress has been extraordinary, but the sort of environmental megatrends that have had some scientists reaching for the ‘Anthropocene’ label for our times threaten to collapse the entire enterprise.

What generation are you?

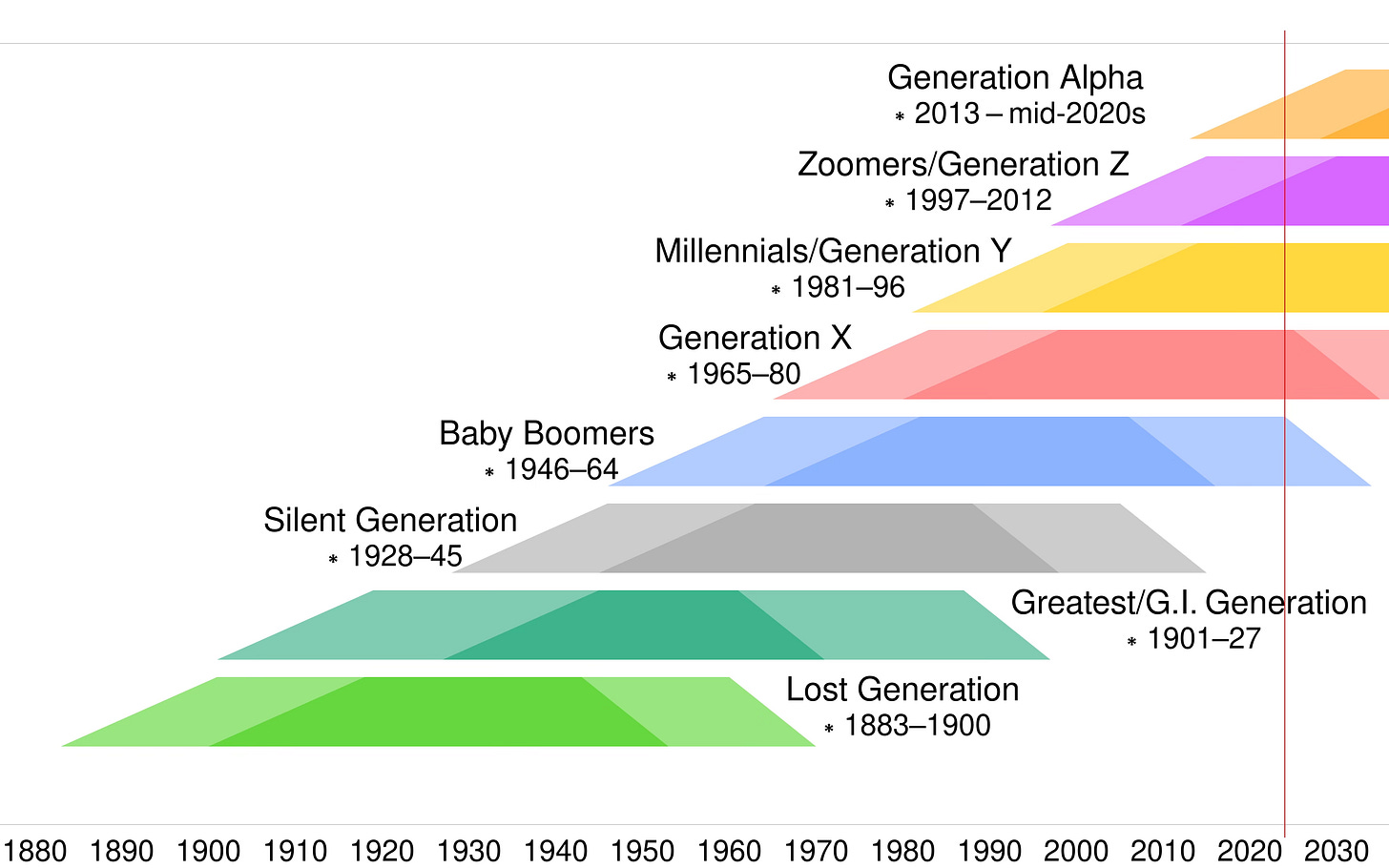

One significant factor in all this has been the adoption of the sort of generational labels and silos that have become central to modern marketing, ranging from the The Greatest Generation, The Baby Boomers, Gen X, Y and Z, and now Gen Alpha. Seductive, indeed I often use the diagram below in presentations, to signal the coming demographic transitions.

As a Boomer, my own shelf life is clearly limited. Meanwhile, much market thinking is fine-tuned to such dynamics, but Guillén now suggests a very different approach. He argues that the sequential model of life has prevailed for 150 years, with every generation told to adopt similar roles and rules, one generation after another. But things have changed—and profoundly.

Today, as life expectancies have stretched, we have eight generations inhabiting the planet simultaneously. In Japan, as many as nine generations now “share the stage.” Some of this is working well, but “frictions are proliferating between longer, taxpaying generations and those in retirement enjoying healthcare and pension benefits.”

As a result, what we used to see as a pan-generational contract, that older generations would care for the young and vice versa, at times seems to be stretching almost to breaking point. The same is true of the assumption that today’s progress would cascade benefits to future generations.

Now, in what Guillén calls the post generational revolution, the dynamics are shifting—with huge potential implications of individuals, communities, companies, economies, societies, and perhaps most fundamentally of all, politics.

The rise of “perennials”

In effect, we seem to be witnessing the proliferation of what Guillén calls—drawing on the thinking of serial entrepreneur Gina Pell—perennials, “an ever-blooming group of people of all ages, stripes, and types who transcend stereotypes and make connections with each other and the world around them.”

A defining characteristics is that “they are not defined by their generation.”

For marketers, increasingly, the challenge will not be to slice up generations up into ever-smaller smaller categories and cohorts—but to seek out the common ground between different generations.

As an example of a perennial, Guillén’s final chapter spotlights a Japanese eighty-year-old, Yuichiro Miura, who had undergone four heart operations and also recovered from a fractured pelvis—and yet who, in 2013, reached the summit of Everest for the third time.

Still, I confess that I feel that Miura-san may have set a rather unrealistic benchmark for the rest of us!

But the central message is clear. We must keep learning, keep evolving. In the book, Peter Drucker, one of the most visionary management consultants of all time, is quoted to the effect that, “we now accept that learning is a lifelong process of keeping abreast of change.”

But half a century after he said that many people—and organizations—still assume that what we learned when we were young will see us through life. “Schools, universities, companies, government agencies, and the entire economy are organized around the classification of people into fixed age groups,” says Guillén. “The system, has served the world well for over a century, but is now itself showing the signs of age.”

He quotes Gary Kopervas, a senior VP at 20nine, a brand agency in Philadelphia: “we find that matching boomers, gen Xers, Millennials and gen Zers in a creative environment leads to a richer and a wider spectrum solution options. If creativity is the goal, creating a multi-generational environment can help fuel better solutions.”

That sounds well worth the effort.

The hardest test of all

But, as a Boomer whose hearing has sometimes found it hard to cope in youthful, high-energy and noisy working environment, because of the combined effects of tinnitus and hyperacusis, my own view is that this will take a fair amount of effort to get right—or right enough.

Indeed, on his penultimate page, Guillén concludes that, “Paying attention to intergenerational sources of conflict over jobs, housing, taxes, healthcare, pensions, and sustainability while transitioning to a better-balanced, flexible society of perennials will be the hardest test of all. Large-scale transformations are never easy or frictionless. In fact, they are characterised by social and political disruption, upheaval, and dislocation.”

“Expect no less this time around,” he says. But his last paragraph notes that the growing numbers of perennials are often best able to ride the waves of change. Wonderful, but the question I am left with is how such people can best change our economic, political and cultural dynamics in such a way that the necessary demographic transitions can be achieved in good time and to good effect?

What readers say:

“John Elkington is unusual in that he has ridden—and helped shape—so many waves of change. But perhaps his central contribution has been in helping to ensure that the tremendous opportunities offered by responsible and sustainable business models are increasingly understood by CEOs and boards.”

PAUL POLMAN, former CEO of Unilever, campaigner, and co-author of Net Positive: How Courageous Companies Thrive by Giving More Than They Take.

Available on Amazon and through good bookshops.

This article gives me hope. We can only solve problems that we recognise. Thanks John, for helping articulating the challenges facing the generations so profoundly.

I believe Perennials hold a wealth of knowledge and experience, yet their potential to influence our economic, political, and cultural dynamics often remains untapped. Their wisdom seems to stay confined within small circles—perhaps shared with grandchildren—while younger generations like Gen Y, Z, and Alpha are engaging (for better or worse) on social media platforms. The visibility and recognition of the wisdom older generations possess seems incredibly low compared to the constant interaction younger generations experience online.

One idea that comes to mind is that a community you create could be a fantastic starting point. You already inspire a wide range of people from all age groups, and I think anyone who has the chance to know you, even a little, would be motivated and inspired by your insights. Your natural character and the inspiration you provide could foster a culture of intergenerational understanding and cooperation. For example, hosting monthly discussion groups where people from different age groups tackle key questions or challenges, sharing knowledge across generations, could be incredibly enriching. The insights or outcomes could even be published as reports or project proposals.

Perhaps it could even evolve into a platform, like a forum, where people from different age groups can continuously engage and share their knowledge.

I'm not sure how accurate my feeling is, since I haven't done any research, but I believe one of the byproducts of today's world is a significant reduction in spaces for debate and thought experiments. With the rise of technology and social media, screen time, passive consumption, and conformity have increased. It feels like the willingness to question, imagine possibilities, or even embrace anarchistic thinking has faded. Even the influence and power of opposition parties globally seem to have diminished. In the 17th and 18th centuries, we had many renowned philosophers engaging in heated debates, but today, despite the growing population, it feels like intellectual engagement has decreased. People seem unhappy with existing systems, yet their desire for change often revolves around improving things within the same system rather than truly reimagining it.