I Pollinate Pineapple - And Vice Versa

Commercial sustainability solutions topped the menu on Pineapple Day

In their wild state, pineapple plants are pollinated by bats and hummingbirds—so maybe (with a hummingbird core to the Volans brand) it was fitting that I was invited to keynote the Pineapple Day 2024 event convened by Andy Dewis’s B Corp, Pineapple Partnerships, co-hosted by lawyers Hogan Lovell.

More accurately, though, I did a fireside chat with Andy, an entrepreneur who built up and sold a climate change and energy business, then joined Schneider Electric as a head of sustainability to help lead a transformation that placed sustainability, the climate transition and partnership at the core of Schneider’s business model.

We met in London’s City, or financial district, with development work going on all around. And we did so on one of the hottest days so far this year, in an auditorium where images of pineapples—together with armfuls of actual pineapples—were all about us.

Which set me thinking about, well, pineapples.

Pineapples love volcanoes

As it happens, the first pineapple plantation I visited, in the last century, was in Queensland, Australia, a region where there were many extinct volcanoes. The second pineapple plantation I visited, in 2022, was in another previously volcanic region, Costa Rica—but this plantation, unusually, was organic.

Near Sarapiquí, we visited Paraíso Organíco, where we were taken around the plantation in a tractor-trailer by the owner’s son, Rolando Soto, Jr. The taste of the organic pineapples he picked and sliced for us in the field that day was, to put it mildly, heavenly. The ensuing Piña colada, when we got back to the ranch, was the best I have yet tasted.

Still, Rolando made it clear that the price premium on organic produce remains a problem—with most producers still stubbornly sticking with the agrochemical model. The Paraíso Organíco farm was started by his father, originally a banker, which may also suggest an even greater hurdle for those with less capital.

And, as a reminder of the default setting, not long after we left the farm we saw a massive sprayer showering chemicals across a field of pineapple plants.

Pineapple Day, take 2

All of this flashed through my mind as I was reflecting on some of the things I had learned during the Pineapple event—itself part of London Climate Action Week.

Once again, the Week had given the London sustainability ecosystem a vigorous stir. The previous evening, for example, I had attended a Google dinner at Goals House in London. The day before that Volans had held its salon on corporate climate advocacy. And horribly early on the Monday morning I had scooted across to the ExCel center in Docklands to take part in the opening plenary session for RESET Connect 2024, billed as the main event of the Week.

It’s intriguing to think through the impact of declaring Days, Weeks, Months, Years and even Decades. As I mentioned from the Pineapple Day stage, I had had personal experience of the game when SustainAbility organized the first Green Consumer Week back in 1988, to launch our million-selling Green Consumer Guide.

At the time, some people thought that we had simply been lucky to get our book out in time to coincide with the Week, not knowing that it was a promotional device. Then, to launch my twentieth book, Green Swans, we organized the world’s first Green Swan Day. Among those who spoke were Sir Smit of the Eden Project, WWF UK CEO Tanya Steele and Mark Campanale of Carbon Tracker.

And now here we were again—celebrating Andy’s second Pineapple Day, as a way of spotlighting the work Pineapple Partnerships are doing in sectors as diverse as social housing and regenerative agriculture.

Ask Pineapple itself to explain what it does, and its website answers: “Our purpose is to facilitate, broker and enable partnerships that deliver transformational impact, at scale. We achieve this by aligning the impact and commercial aspirations of visionary organisations through our three step process, to imagine, build and run.” Some examples of how this works can be found here.

Evolving tomorrow’s markets

Pineapple frames the evolution of partnerships in the sustainability space by linking out to various stages in the development of information technology.

First, they say, came analog technology. “Slow and cumbersome communications technology created a world of competition in which organisations were isolated, reactive and mostly process oriented. Good business meant stand-alone projects as 'corporate social responsibility'.”

Next came the Net. Now, “mobile communications and the internet enabled a world of connection in which organisations were better networked, more proactive and increasingly data driven. Good business meant data-driven decision-making for sustainability.”

More recently, change has been “enabled by cloud technology” … “in a platform world of partnership where organisations are more collaborative, systems-oriented and interdependent. Good business now means working across value chains for system-wide impact.”

Marketplaces evolved and operated in different ways at each of these stages—and will no doubt evolve further and even faster as AI and related technologies surge into the economic mainstream.

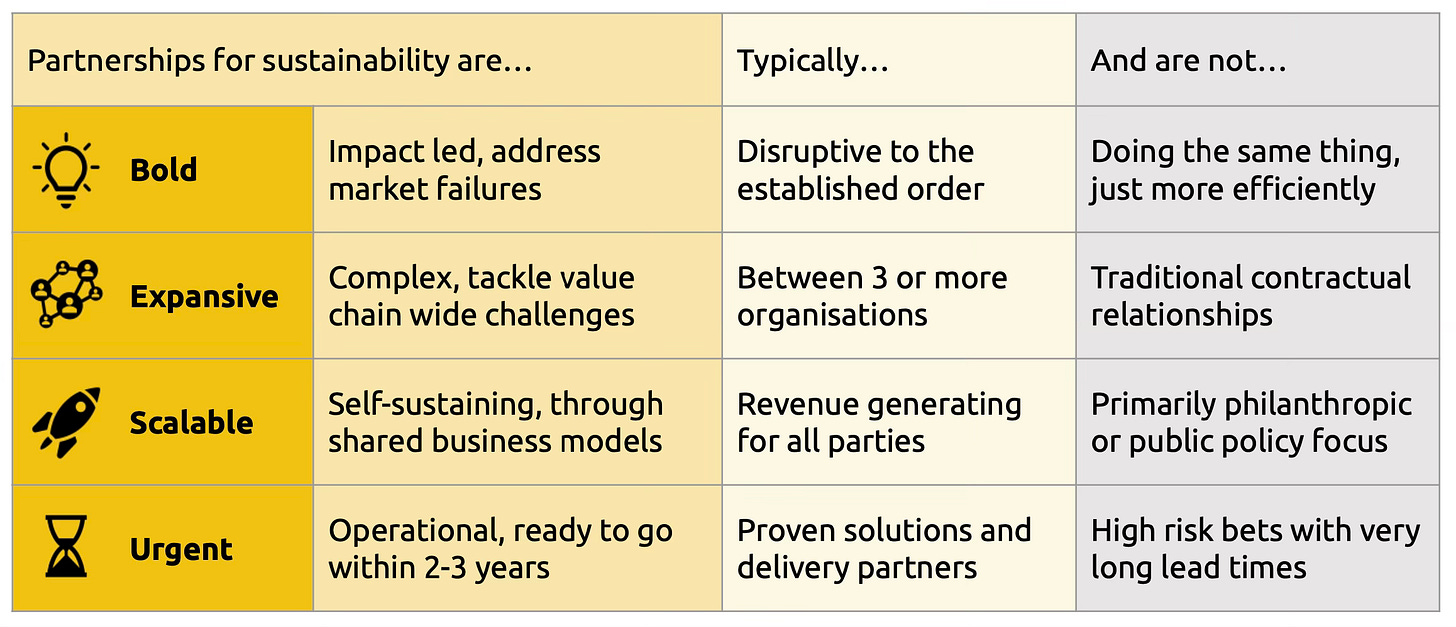

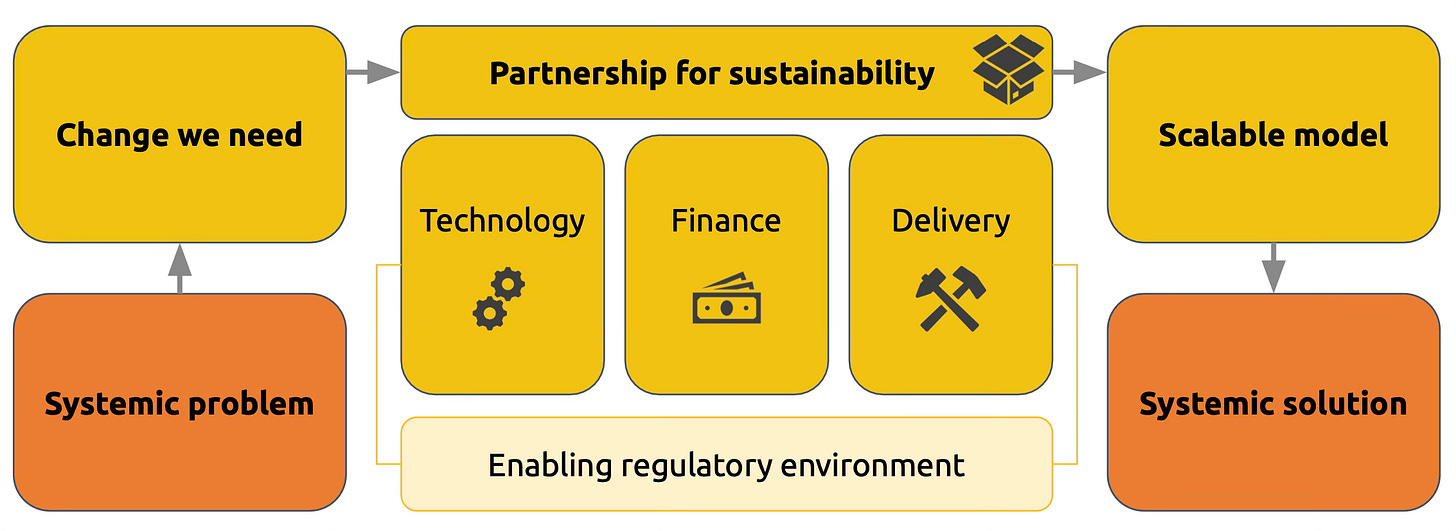

As for the Pineapple model itself, here are two visuals shared on the day. The first explains what successful sustainability partnerships should look like; the second maps the system dynamics they need to bear in mind as they evolve tomorrow’s systemic solutions.

Rewilding markets

In many ways, the second diagram also maps the work I have done via companies like TEST, ENDS, SustainAbility and Volans. But the key element that has been (re)surfacing in my thinking in recent months has been that of the enabling regulatory environment.

In effect, that has been a key part of what we have been exploring via projects like Volans’ Project Breakthrough work with the United Nations Global Compact, with our Green Swans Observatory, and now with this “Rewilding Markets” series of Substack posts.

In retrospect, at least, it is clear that this rethinking process took a significant step forward with my 2018 Harvard Business Review product recall of the triple bottom line—something that was raised with me by several practitioners at the Pineapple Day event.

Once again, as with the triple bottom line back in 1994, a new agenda is fighting its way to the surface in my brain. It’s far from novel, but many of the pioneers are out of sight, out of mind, even for those up to their noses in sustainability.

Very much in the spirit of the “break down silos!” mantra of Pineapple Day, I’m back in the business of hedge-hopping. And the conversations I’m beginning to record here are very much part of that inquiry process.

But…

Tickling Dole

…That said, the commercial history of the pineapple is a cautionary tale which should make us warier of the potential environmental, social and political consequences of the coming economic transitions.

Strikingly, the very symbolism of the pineapple is associated with exoticism, fertility, abundance and wealth on the upside, but also with colonialism, exploitation and conspicuous consumption on the downside.

The way in which people like James Drummond Dole exploited the pineapple to become the “Pineapple King” of his day should give us pause when we try to imagine and build tomorrow’s markets.

Think of the billionaires who exploded out of the New Economy period—Bezos, Gates, Ma, Skoll, Zuckerberg—and then reflect on what the impending Sustainability Transition might do for wealth creation and distribution, for good and ill. It’s easy to talk about social justice and inclusion, but disruptive periods in our history tend to turn existing social orders on their head.

So, very much in the spirit of my new, twenty-first book, Tickling Sharks, I have found myself wondering what it what have been like trying to tickle the Pineapple King?

He was certainly an ambitious entrepreneur. In his investor prospectus in 1901, Dole said that his intent was to “expand the market of Hawaiian Pineapple to every grocery store in the United States.”

A Harvard Man, Dole seems to have been a surprisingly sympathetic character for the era. “We have built this company on quality, on quality, and on quality,” he wrote of the principles of the Hawaiian Pineapple Company. As one profile outs it: “He believed in product safety long before it was mandated, and the company earned a worldwide reputation for quality.”

We also learn that, “Dole was a hands-on manager and knew his employees by name. He frequently left his office to make the rounds. Even when the employees numbered in the thousands, he would introduce himself one-on-one to those he didn’t know. He always believed that those who did the actual work were likely to have the best ideas about how to improve production and quality, and he was always eager to listen to what they told him.”

Actions have consequences

Dole was a pioneer in various senses, it turns out, among other things launching what we would not call a “challenge prize” for early aviators, although with tragic results—in one event three out of eight pilots died.

Whatever we do as entrepreneurs has consequences, good, bad and sometimes ugly, clearly. Yes, it’s possible to find recent analysis suggesting that pineapples have “minimally negative impact,” but the industry’s agrochemical usage ensures that it can have a pretty significant impact on human health and nature.

And the history of the various fruit giants in Central and South America—with the creation of so-called “banana republics”—has often shown capitalism at its worst, at its most shark-like.

Now, with B Corporations like Pineapple Partnerships embracing the triple bottom line, I am more hopeful that we can evolve solutions that create prosperity that is simultaneously economically viable, socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable.

But as smaller-scale, purpose-driven pioneers are bought out—or forced out—of the new sustainability-oriented markets, expect to see the rise of new generations of corporate behemoth, among them China’s giants in areas like rare earth minerals, renewable energy, electric vehicles and robotics.

Monitoring their shark-like behaviours will be even harder than it has been in the West, given that such autocratic countries tend to suppress social and environmental activism. But we must track, monitor and—where sensible—engage them to help shape their thinking and footprints.

Simultaneously, and this is where people like Pineapple Partnerships come in, we must support our own entrepreneurs working to evolve science, technology, business models and future market dynamics that can help us regenerate our economies, societies and biosphere.

And if you want to know more about the evolution of my thinking, my 21st book is a memoir called Tickling Sharks: How We Sold Business on Sustainability (Fast Company Press). Our video trailer can be found here. Available in good book stores and on Amazon, in hardback, paperback, Kindle and audio formats—the last being the first audio version of one of my books that I have voiced myself. Let me know what you think!

Thought-provoking as ever, John. The role of agribusinesses in the banana republics is a shameful episode and rightly highlighted as a reminder that business has an ongoing role to play in ensuring good local governance and human rights.

But I’d caution against a simple equation that seems to be implied of “organic = good; agrochemicals = bad” as it’s more nuanced. On the one hand, organic often means more heavy metals in the resultant crop (and usually more water usage, more disease, along with the lower yields that result in higher cost and therefore higher prices - not helpful when we are trying to feed 8billion people and encourage less meat, more fruit/veg); on the other hand, careful use of well-regarded “agri-chemicals” and agritech can mean the avoidance of these issues. A balanced approach is needed for healthy fruit.