How To Map The Rewilding Of Markets

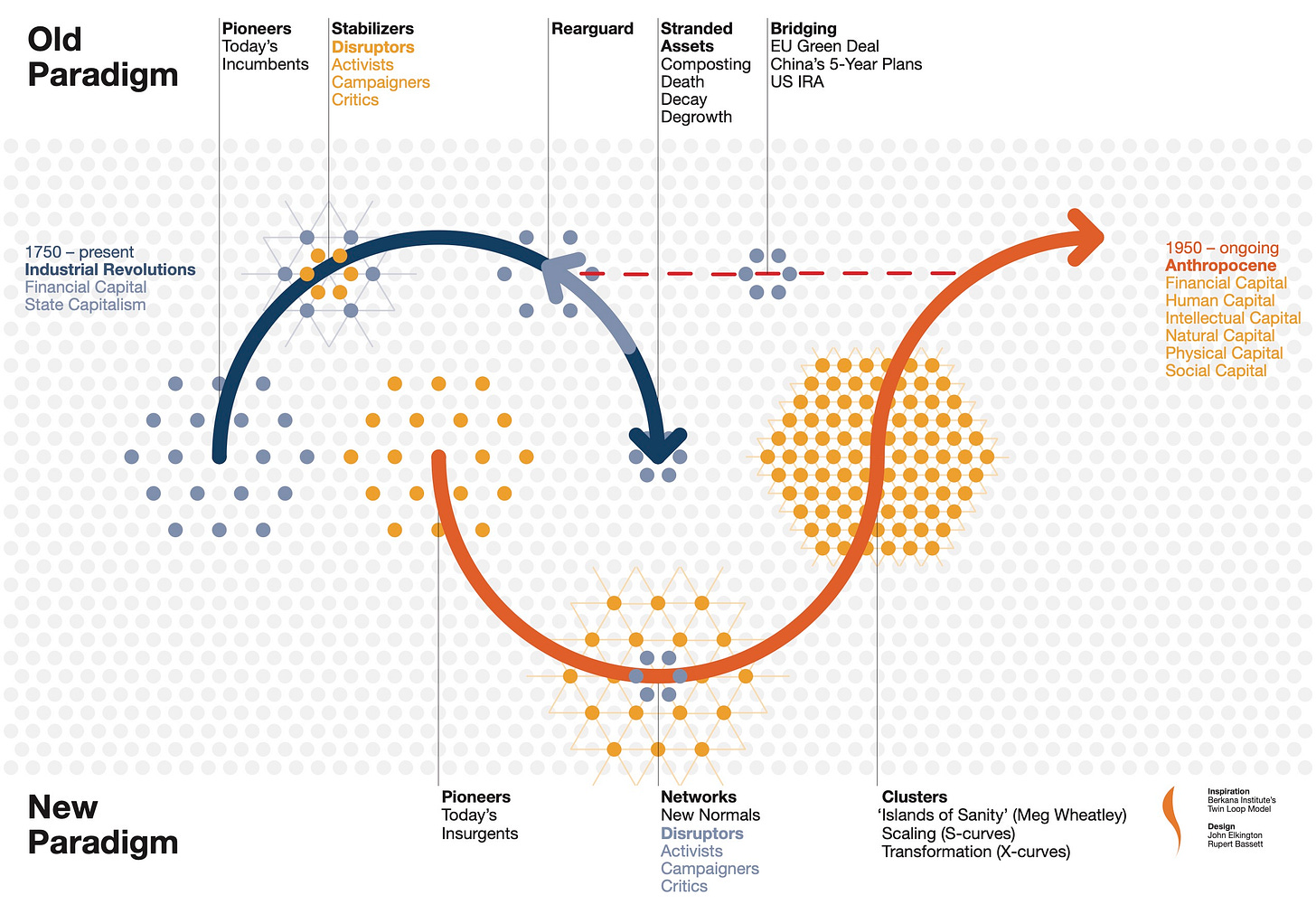

I am playing with the Berkana Institute’s “Two Loops” mapping of system change

My life has been an ongoing story of navigating unknown waters—and charting some of the novel risks and opportunities encountered along the way. Since 1994, I have been evolving a map of societal pressure waves focusing in on a series of societal pressure waves that have progressively impacted governments, business and financial markets since the early 1960s.

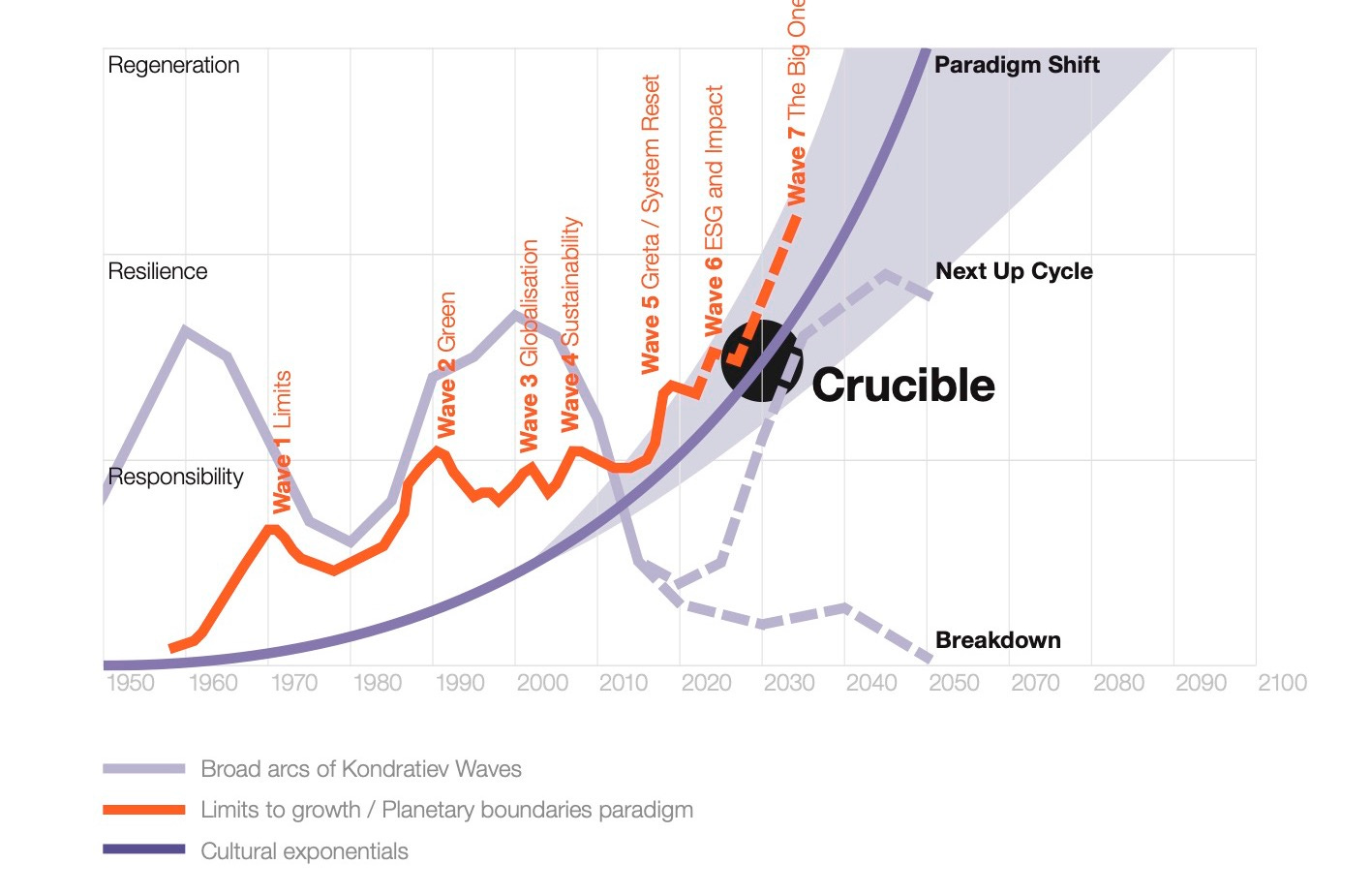

The latest iteration of the Waves Map, as ever co-evolved with my friend Rupert Bassett, tracks several things:

- The “ESG Recession,” as Wave 6 weakens

- An evolving period in which the sustainability agenda becomes both political and politicized (“the Crucible”)

- A potential longer term systemic disruption, the “Big One”

- And, underlying it all, a progressive shift in the prevailing paradigm—indicated by the ongoing debate about whether we are in the Anthropocene or, potentially, working our way toward the Symbiocene.

Loops and paradigms

At the same time, however, I have always been acutely aware that maps are not the landscape—and that they often tell us as much about our own minds and mindsets as they do about the territories charted. So, I have long been fascinated to explore other people’s maps. And, pre-eminent among those, have been various versions of the Berkana Institute’s “Two Loops” Model, also covered in this useful video.

And here’s where I have got in recent weeks, working alongside Rupert. The focus in on paradigm change, something that has fascinated me since I read Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was back in the early 1960s. I have discussed related themes in many of my books—and it is no accident the paradigmatic story underpins my waves mapping.

But one reason why I like the “Two Loops” Model is that it suggests that however many societal pressure waves impact the old paradigm, the old ways of doing things, the main action often happens at the edges, out of view of those in the mainstream.

Maybe you recall these lines from Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring?

Frodo began to feel restless, and the old paths seemed too well-trodden. He looked at maps and wondered what lay beyond their edges: maps made in the Shire showed mostly white spaces beyond its borders.

Now for the blank spaces

It’s time to venture into those white (or blank) spaces—a theme that also surfaced strongly in the recent Sustainability at a Crossroads survey co-run by GlobeScan, the ERM Sustainability Institute and Volans. The three organizations are now co-evolving a follow-up program to explore how radical thinking—and radical solutions—can evolve and help shift the value creation paradigm. More on that shortly.

Meanwhile the top line notes in the diagram below show the Pioneers—the early economists and industrialists—who kicked off the whole process, many now long dead or retired. Ironically, they now find themselves today’s incumbents.

Indeed, I was fascinated by Ha-Joon Chang’s piece in the Financial Times this week, called “How Economics became the Aeroflot of ideas.” That’s behind a paywall, but you can get a pretty good idea of what Chang is saying from this LinkedIn commentary from Hans Stegeman, Chief Economist at Triodos Bank.

Next come the Disruptors (including various forms of activist) who try to change the prevailing system—and the Stabilizers, who try to maintain the status quo by helping it to adapt at the margins.

Now we see the Rearguard fighting back, to protect increasingly existential threats to their strandable assets. As time goes by, a key role for some changemakers will be to “hospice” waning sectors of the economy, helping those adversely affected to make sense of the new order.

Then a new set of Pioneers, today’s insurgents, work to evolve a new paradigm, a new operating code for tomorrow’s Economics and economies. New Networks and New Normals form, some to enable and accelerate the shift, others to slow it down. Next, clusters of innovation and new types of economic activity evolve, as we move deeper into the Anthropocene (even if some scientists struggle to call it that) and, longer term, toward the Symbiocene.

Notes

1. I cleared this version of the Two Loops model with Meg Wheatley of the Berkana Institute, one of the model’s originators. The one thing she suggested that I add, which you will now see in the bottom “New Paradigm” line, was the thought that what I have called “Clusters,” because I’m thinking about the evolution of economies, she calls “Islands of Sanity.” They mean different things, I believe, but can also be complementary if we decide to make them so—with her version helping to provide the cultural and political context within which future clusters form.

2. I plan to take August off, among other things to work on my next book, now provisionally called The Invisible Paw: Rewilding Economics. I may have bitten off more than I can chew here but am determined to push the envelope as far as I can with the mental resources at my disposal. Whether we think in terms of the waves (as in the first map) or of paradigm shifts (in both maps), the rewriting of the operating code on which pretty much all our modern economies now run must be job #1.

What readers say:

“John is a legend. Throughout my 30-year career in sustainability leadership, he has been a source of insight and inspiration. By extension he has influenced the thinking of thousands of senior executives on our programmes. This book offers a wonderful and personal reflection on the evolution of the sustainability movement and glimpses of what might be to come.”

DAME POLLY COURTICE, founding director, Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL)

Beautifully framed, John. Your post brought me back to Wheatley’s wisdom and the quiet but strategic power of hospicing what no longer serves.

Like in nature, where old structures return nutrients to the soil, honoring systems that once worked well but no longer do can release talent, insight, and energy to nourish what’s next.

Too often in the sustainability movement, we’ve rushed to reject the past without recognizing the value it once created or the people still holding it. But hospicing isn’t just charity; it can be catalytic. Sometimes the fastest way to grow the new is to honor what got us here and reinvest its strengths in what comes next. (cross-commented on LinkedIn)

https://hls.harvard.edu/bibliography/the-edges-of-the-field-lessons-on-the-obligations-of-ownership/