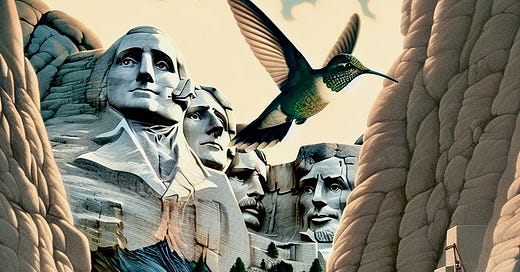

A Mount Rushmore For Sustainability?

Who would you want included? One of my votes would go to Richard Sandor.

It’s some decades since I visited Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills that rise up from America’s Great Plains—and then, seventeen miles to the southwest, we also dropped in on the evolving monument to one of my all-time heroes, Crazy Horse.

To be honest, I have never quite fathomed what the Oglala Sioux shaman and war leader might have made of his one-time enemies dynamiting a mountain in his memory, but a recent conversation with a living hero had me wondering who we might short-list for a sustainability-themed version of Mount Rushmore? Alongside, say, Rachel Carson, Gro Harlem Brundtland, or Denis Hayes?

In my pursuit of people with a deep understanding of how to tune markets to solve sustainability challenges—in this case a life-long passion for markets—one name sprang to mind very early on.

He and I first met when we were part of the founding group, convened by Sustainable Asset Management (SAM) in Switzerland and Dow Jones Indexes in the USA, for the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI)—a family of best-in-class corporate benchmarks now owned and operated by S&P. Some of the stepping stones are sketched here. I served nine years on the DJSI advisory board, helping push me further up the learning curve in relation to financial markets.

The DJSI approach, which integrated my triple bottom line framework from the outset, had a huge impact. I remember any number of companies conceding that the entry of Dow Jones into the fray elevated sustainability to a different level with their top teams. The limitations of the approach, though, were underscored when DJSI celebrated Volkswagen as a sustainability sector leader a few weeks before the Dieselgate scandal broke.

Despite such glitches, however, the DJSI initiative proved to be a powerful market catalyst. But, as was so often the case at the time, the focus was on companies rather than on the wider markets they aimed to serve—or at least to profit from.

Richard already understood markets way better than I ever will. But one thing I particularly remember about him at that time, particularly when I visited him in his Chicago offices, was his parallel passion for photography. He and his wife Ellen have accumulated the most extraordinary collection—covering everything from historic moments like the Wright Brothers’ early experiments in heavier-than-air flight, Paris in the Twenties, Hollywood glamor, African-American visions, the rise of feminism, and outsider art.

Still, given my current quest for clues on how we might redesign today’s markets and better design tomorrow’s, I was keen to learn what lessons he had learned in a career which is significantly longer than mine. Now aged 83, he kindly kicked off by describing me—at a mere 74—as “a kid.” But, whatever our ages, we share way more than his passion for photography and the environment. As he put it part-way through, “we share the same DNA.”

When I asked him how he would describe himself, he said: “I’m a problem-solver. I see a problem and I think how to fix it.” But, he noted, it’s rarely a straight-line process. “You crash into a wall, pick yourself up, assess why all that happened, then crash into it again. Then, after a while, the wall either moves or collapses.”

It’s probably easier to say what this man hasn’t done than what he has, but let’s attempt the task in two paragraphs.

First, then, his impact on mainstream finance. As a professor on sabbatical from the UC Berkeley in the 1970s, Richard became the chief economist at the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT). There he not only pioneered the first interest rate futures contract, but also the most widely traded and imitated interest-rate futures in the world, the Treasury bond futures contract. This, as his Wikipedia entry notes, “revolutionized the field of finance and earned him the title of ‘father of financial futures.’” As if that were not enough, he also coined the term "derivatives" to describe the futures and options contracts traded on the Chicago exchanges. He was honored by the CBOT and City of Chicago in 1992 for the creation of financial futures.

But, second, the reason I first came across Richard was his work on emissions trading—an area which he also pioneered. Using his firm Environmental Financial Products (EFP) as the incubator, Sandor founded the Climate Exchange PLC (CLE) family of companies. They include the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX); the Chicago Climate Futures Exchange (CCFE); and the European Climate Exchange (ECX), Europe's leading exchange operating in the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) and the benchmark for world carbon prices. In addition, he and EFP turned their attention to the feasibility of a market-based mechanism as a tool to address water quality and quantity issues.

All of this has not gone unnoticed. In August 2002, for example, he was chosen by Time magazine as one of its "Heroes for the Planet" for his work as the founder of the Chicago Climate Exchange. Then, five years later, he appeared in Timemagazine's fifth annual list of "Heroes of the Environment" for his work as "the father of carbon trading."

He believes in markets, clearly. And when I ask what he teaches his students, he notes that a basic question he asks is whether taxes or markets are better when addressing social and environmental challenges? He invites students to come up with market-based solutions to externalities of their choice.

So, what sort of externalities do they try to address, I ask. He says they have tackled everything from space junk to the carbon content of discarded fashion, alongside the question how to optimise the use of prisons, even across national borders, and the allocation of judicial appointments.

At this point I started to get just a little edgy. I expressed concern about the potential “marketisation” of key features of our societies where markets seem likely to misdirect our attention and resources. Given that I live in London, the appalling recent financial and environmental performance of water companies like Thames Water was very much in my mind. The annual Oxford-Cambridge boat race ends just around the corner from us in Barnes—and this year several rowers suffered health problems attributed to sewage in the river.

Richard countered that markets only work if properly regulated. I then shared my nuclear analogy, noting that markets are like the incandescent cores of nuclear reactors, needing thick layers of lead, steel and concrete to shield the wider world from harm, alongside complex systems supplying things like information, electricity and water.

He riffed off the idea, agreeing that markets are fundamentally unstable as they generate various forms of value—and linked externalities. When things do go wrong, as they did in the economic crisis of 2007-9, the economic, social and environmental equivalents of radioactivity are sprayed over the wider landscape.

The core problem, Richard said, is that rent-seekers often oppose the construction of sensible regulatory guardrails, or seek to weaken or remove them where they exist. Clearly, they do this to maximize their short-term profits, but in the process risk undermining the stability and safety of the entire system.

Richard has long honoured his friendship with his mentor, the Nobel Prize-winning British economist Ronald Coase, a Nobel Prize-winner for economics. Even back then, Richard recalls, Coase was concerned about the direction of the whole economics profession. At the same time, however, he was acutely alert to the fact that creating new markets tends to be challenging.

His advice to Richard: “Think of failure as one result from a clinical trial.” Disappointing, yes, but not terminal. And, his mentee now recalls, a valuable reminder of just how difficult designing—or redesigning—markets can be. Happily in terms of my current learning curve, his book, Good Derivatives, is in the post.

So, while I’m not in favour of blasting away mountain tops to create public monuments to great people, and would see a sustainability version of Mount Rushmore as even less appropriate than Polish-American sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski’s celebration of the life of Crazy Horse, these have been some of the reasons why Richard Sandor would be on my shortlist for something along these tracks.

And that t-word reminds me of his parting comment on my desire to expand the scope of our work from brands, businesses and their supply chains to wider market dynamics. Unprompted, he concluded: “You’re on the right track!” A generosity of spirit that provides yet one more reason why one sculpted head in my mental image of that alternate Mount Rushmore wears a fedora.

wonderful article and Doc is no ghost daner as his work and his wisdom are very transparent